2020 | Budongo Forest Reserve, Uganda

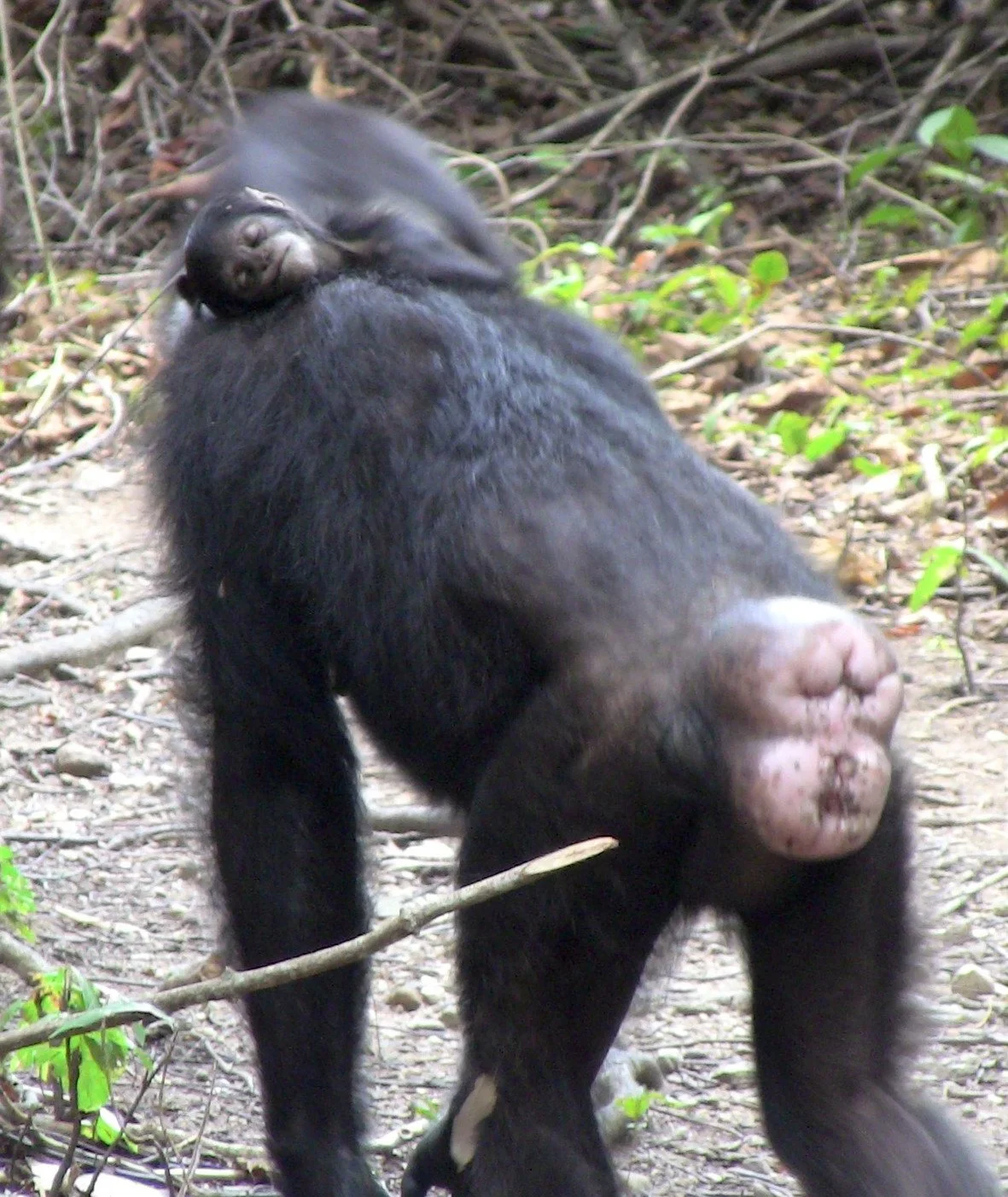

Chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes schweinfurthii) dead infant carrying

Humans are animals. In the past this simple truth has been difficult for some people to accept, but it’s the key to setting our own behaviour in its wider biological context. And it raises new questions and pathways for understanding our fellow creatures.

One fascinating new research field looks at how other animals react to death. For example, what commonalities and differences do they have with us, as they grieve (or don’t) for their lost relatives and friends? Have they developed rituals or specific behaviours around the dying or dead, or does death flick a switch that turns a conspecific into an uninteresting object? It’s much too big a topic to cover in full detail here, but if you want to know more about this work as it emerges, I strongly recommend the writings of authors and researchers Barbara King and Susana Monsó.

Today we’re focusing on just one sliver of that turn towards death. Our subjects are the chimpanzee communities of the Budongo Forest in Uganda, which have been continually studied since 1990. In particular, we will be asking whether one chimpanzee mother used a tool—a twig—as part of the grieving process for her deceased infant.

Endgame

Scientists studying how animals perceive and react to death have named their field ‘comparative thanatology’. The term thanatology has the same origin as that of Marvel villain Thanos, with both based on the ancient Greek personification of death Thanatos (son of night and brother of sleep).

Thanatologists record and interpret the ways that animal behaviour changes around dead and dying group-mates. They’ve investigated ants, crows, dolphins and elephants, and more. Their findings are mixed: in some cases dead nest-mates are treated as simply material to be removed. In other instances it seems as though those still living don’t understand or recognise that their companion can no longer respond, that a fundamental change has occurred. But they’ve also found times that the care and attention that other animals give to deceased relatives has familiar hallmarks from our own experience: an awareness of the changed nature of a dead animal, for example, or recognition that the previous partnership between the living and newly-dead can no longer continue.

One of the better-studied instances of this behaviour is when wild chimpanzee mothers carry their infants for extended periods after the child’s death. For several years, Elizabeth Lonsdorf of Emory University and her colleagues watched as mothers and others at Gombe (the east African site made famous by Jane Goodall’s research) regularly kept hold of dead infants as they continued about their daily routines. Lonsdorf recorded 33 cases of what they call ‘infant corpse carrying’, ranging from less than a day of carrying to over two weeks. In every instance where a mother could take her infant with her after its death—excluding those times when an infant was taken and killed by another chimpanzee or humans—the mother did so.

Here’s one of the Gombe chimpanzees carrying her deceased child over her neck, in a way that isn’t normal for a live infant. This atypical behaviour might reveal that the mother knows her child has changed from its live state, and can no longer hold on for itself:

Gombe isn’t an outlier in these kinds of behaviour. At the Bossou site in west Africa, Dora Biro and her team reported that two chimpanzees were seen carrying dead infants after a respiratory epidemic broke out in late 2003. One of the mothers carried her child for 68 days after death—almost 10 weeks—while the other transported her child’s corpse for 19 days. Like at Gombe, these chimpanzees carried their infants in ways that were not typical for a living child, including clasped in their hand or foot or carried across their neck or back.

The Bossou chimpanzees also made use of tools as part of their treatment of the dead, seen in this video from Biro’s report, with mother Vuavua picking up a nearby twig to swat flies away from the body of her infant Veve:

I’ve included a second video from Biro and her colleagues at the end of this post, in which the dead infant’s mother cracks nuts with stone tools while another young chimpanzee plays with her child’s mummified body. Tool use around dead children seems to be a part of Bossou life.

Substitution

Which brings us back to the Budongo case study. Like the scientists at Gombe and Bossou, Adrian Soldati of the University of St Andrews assembled a collection of observations around two chimpanzee communities in the forest—the Sonso and Waibira groups.

The Budongo team were interested in several hypotheses about why chimpanzee mothers continued carrying their children after death. Given the physical changes, especially mummification, and lack of response from the infants, what prompted this interaction with the deceased? They identified three main groups of theories:

The ‘unawareness’ hypothesis suggests that the mothers don’t recognise that their children have died, and they continue providing care as if to a living infant. In this theory, underlying hormonal pressure on the mother is a possible mechanism driving the behaviour.

The ‘learning about death’ and ‘grief management’ hypotheses both suggest that chimpanzees interact with dead community members to build up their understanding of death, and reduce the stress that builds up at times of loss. These theories assume that chimpanzees have at least some notion of the difference between alive and dead.

The third group of hypotheses focus on the development of mothering skills, whereby younger or new mothers look after the deceased child as a way of practicing the behaviour necessary to raise a child (whether or not they recognise the child as dead). Similarly, the ‘maternal-bond strength’ hypothesis predicts that mothers build up a connection with older infants that is not easily broken at death.

Across a combined 40 years of observation, the researchers found that 68 of the 191 chimpanzees born at Budongo died in infancy (defined as five years old or less). Twelve of those infants were seen being carried by their mothers, for periods ranging from one to 89 days, although most were carried for a few days only. Most of the carried infants were aged less than a month when they died. The team also note that their data likely underestimate the prevalence of this behaviour, given their inability to follow each of the wild animals at all times.

As I mentioned at the top of the post, we’re looking at one particular chimpanzee mother from the study. Her name is Upesi, meaning ‘fast’ in Swahili. Here she is in 2013, shortly after joining the Sonso community:

At the time of interest in 2020 she was around 21 years old. At that point her two known previous children had each died at less than a month old, in 2017 and 2018, both killed by other members of the Sonso group. Her third child was born in late September 2020, and unfortunately it too died a few days later, although the cause of death wasn’t clear this time.

The researchers first saw Upesi carrying her dead infant on 25 September, and from then until 19 November she continued to move around with the corpse. As with chimpanzee mothers at other sites, she held the child in her hands while walking, and tucked into the pocket of her upper leg when climbing or moving about in the trees. During that time the infant mummified in the forest climate.

On 23 November the team saw that she was no longer holding her child. Instead, Upesi carried a twig about half a metre long in her mouth. Just as she had done with her infant, she transferred the twig to her leg pocket when she needed to free up her hands for climbing or other tasks. And for the next two weeks she continued to carry a twig (it’s not certain that it was the same stick or a similar one) everywhere the group went, including during patrols of several kilometres through the Sonso territory. The observers never saw her put it down.

In this video from the report by Soldati and his colleagues, Upesi approaches with the twig in her mouth, tucks it away while drinking water, then leaves still holding the object. Her movements are quick, so you may need to watch it a few times to get the full sequence:

The team didn’t see Upesi from the end of the first week of December until late January 2021, by which time she was carrying neither her child nor the stick. Soldati and his colleagues report that the twig:

may have been used as a substitute for her dead infant’s body…Upesi’s behaviour was observed multiple times over several weeks, and…she was not seen interacting with the object, treating it instead in the same way as she had her infant’s corpse. Thus, object carrying may also be associated with the loss of an infant in bereaved chimpanzee mothers.

It is not common for Budongo chimpanzees to carry twigs. None have ever been seen carrying anything but food from one place to another, and Upesi clearly wasn’t eating the stick. Instead, it seems she was taking some care not to lose or damage it. Unlike many other chimpanzee communities, the Budongo group also don’t use stick tools for foraging, even when prompted to do so by field experiments set up by the scientists.

In the wider context of hypotheses for infant carrying after death, Upesi’s case does not support the theory that chimpanzee mothers are unaware that their children have died, and simply carry on tending them. Upesi transferring her attention from a changed but still recognisably chimpanzee infant to a foreign inanimate object cannot be explained by suggesting that she didn’t understand that the infant had died. However, both the second and third set of hypotheses listed above, around grief management and maternal bonds, make more sense in this context. The research team follow this line of reasoning, emphasising the bond between mother and infant and reviewing the whole dataset from Budongo to conclude that:

our observations support the argument that these mothers act as if they are aware of the loss but continue to display a strong attachment to the bodies of their infants and may be affected by psychological processes akin to human grieving.

Tools and troubles

Upesi’s behaviour was unique and unexpected for her chimpanzee community. Still, if this was a case of the mother using an object as a coping mechanism for the loss of her child, it would mirror similar behaviour seen in humans, and even reported for other animals such as beluga whales. It also recalls the use of ‘dolls’ by both wild chimpanzees and orangutans, in which typically juvenile females hold and tend to leaf bundles and other plant material in an echo of the later maternal role they will play. Of course, a human fascination with dolls and the care shown towards them by young children is commonplace in many societies, but as yet it’s unknown how far back this activity goes into our evolutionary past.

As with all unique observations of animal tool use—from a bereaved chimpanzee possibly carrying a child substitute to a puffin touching itself with a stick—it is extremely difficult to draw wider conclusions from the initial report. Upesi’s behaviour does draw our attention to a perhaps overlooked ability or tendency within our ape cousins, though. At some point humans began to imbue inanimate objects with their own sets of desires or wants, and to draw those objects into our exclusive social circles. Is the same instinct present in other animals, and to what extent? How would be recognise it if so? As with everything we once thought separated us from other species, we should expect future discoveries in the way that animals react to death to reveal nuances that continue to blur the lines between us and them.

Further viewing

Please note: this video of the Bossou chimpanzee community contains scenes that might distress some viewers. It shows young chimpanzee Fokayé playing with the mummified body of fellow infant Jimato, while Jimato’s mother (Jire, left) and Fokayé’s mother (Fotaiu) crack palm nuts using stone tools. The video was part of Dora Biro’s research at this west African site, discussed above.

Sources: Lonsdorf, E. et al. (2020) Why chimpanzees carry dead infants: an empirical assessment of existing hypotheses. Royal Society Open Science 7:200931. || Gonçalves, A. & D. Biro (2018) Comparative thanatology, an integrative approach: exploring sensory/cognitive aspects of death recognition in vertebrates and invertebrates. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 373:20170263. || Biro, D. et al. (2010) Chimpanzee mothers at Bossou, Guinea carry the mummified remains of their dead infants. Current Biology 20:R351-R352. || Soldati, A. et al. (2022) Dead-infant carrying by chimpanzee mothers in the Budongo Forest. Primates doi:10.1007/s10329-022-00999-x. || Hobaiter, C. et al. (2020) Sonso Community Chimpanzees; http://www.budongo.org/media/1311/2020_04-official-list-sonso-chimpanzees.pdf

Main image credit: Soldati et al. (2022) || Second image credit: Lonsdorf et al. (2020) || First video credit: Biro et al. (2010) || Third image credit: Corinne Ackermann; https://budongo.wordpress.com || Second video credit: Soldati et al. (2022) || Third video credit: Biro et al. (2010)