2012 | Piak Nam Yai, Thailand

Long-tailed macaque (Macaca fascicularis aurea) crab hunting

Usually in this blog I cover the amazing animal research of other scientists. But today’s topic is a little different, because it’s based on one of my own recent studies. It involves a wild monkey, an aggressive crab, and the first known use of a stone hunting weapon by any non-human animal.

What Judas did next

My work trying to understand how animal tool-use evolves has taken me to field sites around the planet, from chimpanzees in Guinea, bearded capuchins in Brazil, and long-tailed macaques in Thailand, to sea otters in the USA and crows in New Caledonia (not to mention dozens of human and hominin archaeological digs). In Thailand, my long-term collaborators are Suchinda Malaivijitnond of Bangkok’s Chulalongkorn University, and Michael Gumert of Nanyang Technological University in Singapore. Both are experts in macaque behaviour and co-authors on our paper, published online in September 2022 in the journal Behaviour.

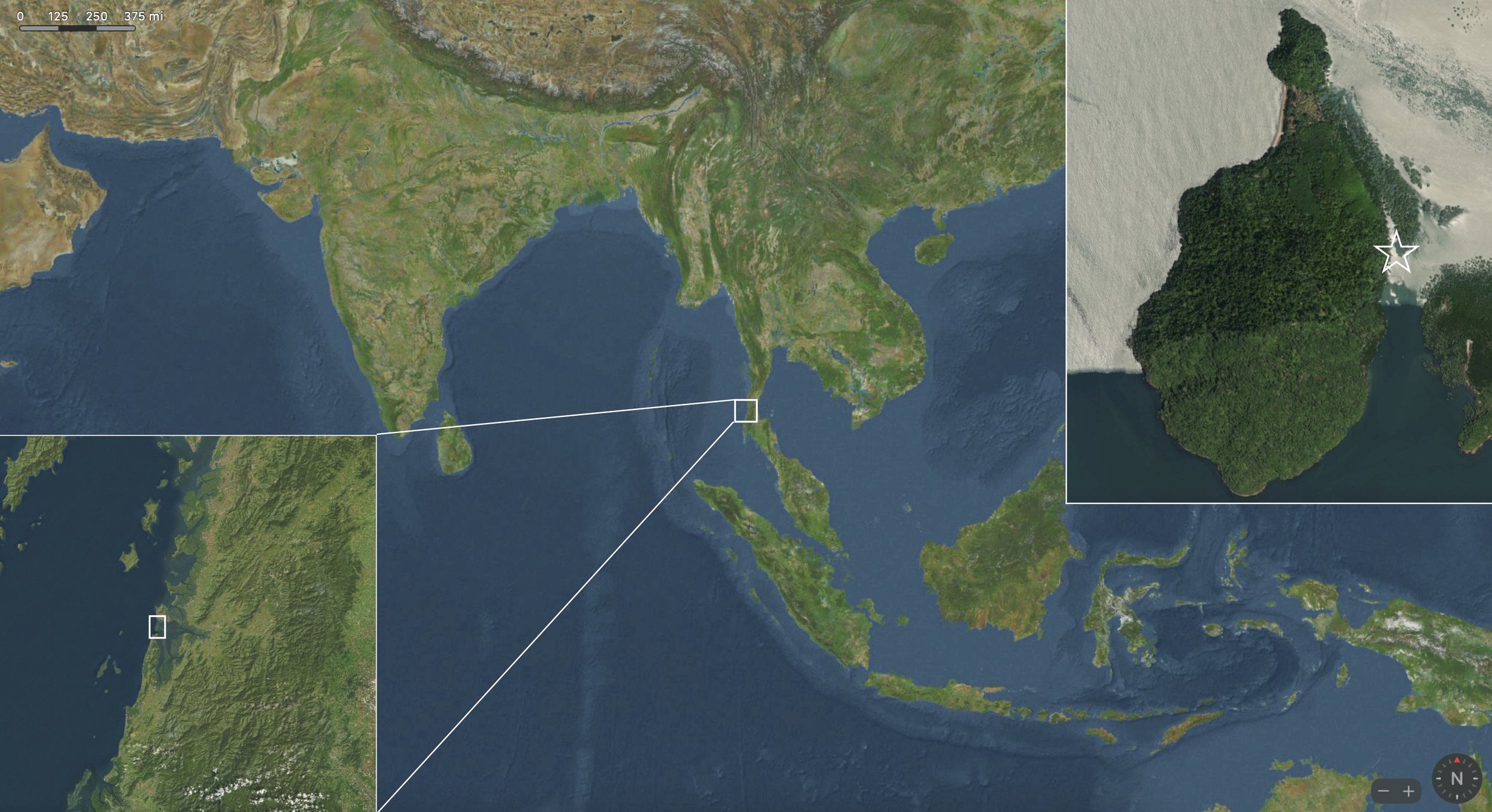

Stone-tool-using macaques (Macaca fascicularis aurea) live exclusively on islands off both sides of the thin peninsula that includes southern Thailand and Malaysia. The best-studied monkey groups are found on Piak Nam Yai, a small coastal island in the Andaman Sea. And the incident we’re talking about today—the incident with the crab—happened in a small tidal inlet on the northeast of Piak Nam Yai. The inlet is surrounded by mangroves, marked with a star as we zoom in on the map:

That inlet was part of the territory of a monkey group known, for obvious reasons, as the Mangrove Group. One of the group’s adult males was named Judas by Dr Gumert—all the monkeys were named by him as he worked to differentiate them and record their behavioural patterns. Judas was a fairly typical male macaque, sometimes using handheld stone tools to break into oysters attached to the exposed rocks, and occasionally using a stone anvil and hammer combination to crack open a gastropod. That’s him, all blurry in the photo at the top of this post.

One Wednesday (23 May 2012 as it happens) Michael and I were in a small boat just offshore from Piak Nam Yai. This was our usual workplace, and we’d been out since high tide, watching the island’s coast as the various monkey groups gradually descended from the steeply forested interior. Typically one or two older leaders would make the first moves from the trees out onto the more exposed shore, before the rest of the group began an afternoon’s steady cracking and munching of shellfish. The macaques kept an eye on us, but as long as we didn’t approach in the boat they were happy to go about their day

Just before 6pm, as the daylight began to fade, I noticed a monkey hurrying up from the muddy area that had been revealed by the lowering tide, using a three-legged gait while clutching something to its chest. I had a Sony Handycam video camera, but no ability to stabilise the rocking of the boat or my own hand movements, which were amplified by the fact that I had to zoom in all the way to capture the action. This was a decade ago, so unfortunately no 4K digital clarity either.

With apologies for the movement, then, this is what I filmed:

What you see is Judas standing over a large, flat basalt rock, while trying to manipulate and flip an orange mud crab (Scylla olivaceae). Judas has brought the crab to the rock from the place he’d initially captured it, further out on the mudflats. Usually a monkey would bite or tear apart the crab until it stopped moving, and only afterwards would they sometimes use a stone hammer to break into the tough claws. But here was something different.

The crab is clearly dangerous, standing with its pincers raised and getting in a good nip on Judas’ left hand. What the macaque is trying to do is subdue the crab using the stone—essentially knocking it out with a very large weapon. His first attempt misses, despite taking all his bodily strength to raise and smash the stone down. Only as the crab tires does Judas eventually manage to flip it on its back for long enough to strike with a second blow. The crab goes limp, and Judas picks it up and walks away.

It’s not in the video, but after walking several metres Judas sat down and ate the crab, without again using tools at any point. Here he is enjoying his hard-earned snack while other group members forage around him:

Hunter/gatherer

So, why is this special? And why call it hunting? As Suchinda, Michael and I noted in our paper:

Hunting refers to any animal activity that involves chasing and subduing another animal to kill or injure it…While Judas’ initial capture of the crab at Piak Nam Yai was not filmed, the recorded segment of the subduing phase is heavily dependent on his use of a large stone hammer. In this respect the macaque behaviour mirrors much human hunting, in which the initial stalk and chase may be done on foot, but a weapon (spear, club, knife, etc.) is then used to incapacitate or kill.

Judas wasn’t trying to break apart the crab—he did that later without using tools—he was trying to manage a desperate and dangerous crustacean. This is the critical stage of the hunt, when the prey is cornered but uninjured. It is free to fight back. Not all hunts need tools, and in fact most crab hunts on Piak Nam Yai are completed by the monkey using brute force to kill the crab. That’s why we decided to call Judas’ actions ‘tool-assisted hunting’, to emphasise the unusual nature of this particular capture.

Going through the animal literature, we found that this is the first time anyone has seen a wild animal use a stone tool to hunt another animal. Humans and our ancestors have used stone tools to hunt for millennia, but it was one of those things supposedly unique to us. Judas changed that.

There are examples of other types of tools used by wild animals to hunt. Chimpanzees in Senegal make and use wooden spears to subdue bushbabies or galagos, and dolphins off the west Australian coast use marine sponges to help hunt down fish hidden in the sandy seabed. I’ve also seen how Brazilian bearded capuchins use stones to break apart the soil as they dig for spiders and roots. But Judas is the first that we know of to use a stone tool to actually attack his living prey in an attempt to stop it attacking him.

I should say that this is, to date, a one-off observation. There’s no sign that the macaques of Piak Nam Yai are now organising their hunts around stone weapons. It may be that Judas was the first and last of his kind to do so. But it does show that behaviour that came to define the human lineage—hunting with stone tools—can appear sporadically elsewhere.

A crucial step taken by our ancestors was that they began hunting more and more dangerous prey, prey that could and did fight back. In contrast, most stone tool use by animals is directed at unmoving targets: nuts, eggs, even the oysters favoured by the Thai macaques. The risks involved in taking on food that fights back mean that it is not often a sensible choice, and Judas may have figuratively bitten off more than he could literally chew.

What he has given us, at least, is another viewpoint from which to assess our own technological choices. And another reason to get back in a small boat and head out into the warm Andaman Sea.

Source: Haslam, M et al. (2022) Stone-tool-assisted hunting by a wild monkey (Macaca fascicularis aurea). Behaviour doi:10.1163/1568539X-bja10174

Images and video credits: Haslam et al. (2022); M. Haslam, based on Apple Maps data