Tools of attraction

Dolphins, monkeys & bowerbirds…

Today we’re visiting three different battlegrounds in the natural struggle for existence. However, the battles we’re interested in aren’t violent (well, mostly). Instead, they’re the kind of duel that’s been fought for almost as long as there has been complex life on this planet, in which males and females come together to try and reach agreement on the most important of biological topics. Mating.

Each of the three species below has taken to using objects to warm up the opposite sex. Carrying, throwing and displaying these objects is part of their engagement strategy, whether as an idiosyncrasy, a group tradition, or a species-wide trait. This is tool use, in service not of a better meal or a more comfortable life, but as a means to life itself.

1. Pool toys

We’ll start in the water, with Australian humpback dolphins (Sousa sahulensis) off the island continent’s northwestern coast. Other species of dolphins in the region are known to use tools for foraging, whether by trapping prey in a shell, or using a sponge to protect their beak while scrabbling in the sandy seabed. That sponge-tool use is concentrated in particular lineages of female dolphins, and can be tracked back through the generations using DNA.

Starting in April 2010, however, the Sousa dolphins seemed to be up to something different. Adult dolphins would appear at the surface with a marine sponge, but rather than then diving with it to the ocean floor, they displayed it, or even tossed it into the air. And to add to the oddity, each of those displaying dolphins was male. Food clearly wasn’t on their minds, since they typically directed their attention towards nearby females (with weaning-age calves)—when the dolphins tossed the sponges, it was repeatedly in the direction of those females.

Here’s an example of the activity, with the male on the right carrying a large sponge:

The team documenting the behaviour, led by Simon Allen of the University of Western Australia, concluded that the display was not just attention-getting foreplay, but might contain clues to the prowess of the spongy males. In their 2017 report, Allen and his colleagues noted that gathering sponges could be a difficult task, and the sponges might even fight back, with the result that:

Sponges may therefore require dexterity and strength to remove, while conceivably exposing the dolphin to both discomfort from chemical defences and greater risk of shark attack while otherwise engaged. Obtaining and presenting the sponge may also represent a signal of cognitive ability.

This would be survival of the smartest, or perhaps bravest. However, the team do have alternative ideas, although they are less congenial. For example, the males may be aggressively intimidating the females as part of a coercion attempt: survival of the bully. In either case, this is tool use, where the object changes the natural abilities of the male dolphins to influence their mating prospects.

The scientists saw this behaviour 17 times over a decade-long survey along 1,500km of the Western Australian coastline. Obviously, that’s an enormous area to cover, so this is likely just the start of our understanding of what these gifting/threatening males may be up to. Keep your eyes peeled for more on this in the coming years.

In the meantime, enjoy this short interview with Simon Allen and footage of those amorous dolphins:

2. Rocky relationships

Male dolphins may have a difficult time getting the attention of dolphin ladies, but what if the opposite were true? When a female bearded capuchin monkey (Sapajus libidinosus) is ready to mate—known as her proceptive phase—often the hardest part is getting noticed by their preferred male. Across a series of days, females will follow a male around, making faces at him, touching him, pulling his tail, and increasingly foregoing feeding and other activities. The male capuchin, on the other hand, just goes about his day. To an observer, the frustration of the female is palpable.

In 2013, Tiago Falotico and Eduardo Ottoni of the University of São Paulo reported on one group of wild capuchin females that had ratcheted up their approach. Falotico followed this group, in Serra da Capivara National Park, Brazil, for almost 1300 hours as part of his PhD research. He watched as three of the proceptive females picked up and then threw stones at their target, which was always a high-ranking male capuchin, on 52 separate occasions.

Here’s one of those instances from the report, with a female named Pedrita picking up a stone before standing and launching it left-handed towards the target male (Bochechudo). Perdita was the stone-throwing expert in the group:

The Serra da Capivara capuchins are well known for using stones to break open nuts and seeds, as well as for digging in the sandy soil to reach tasty spiders and tubers. A few years ago my team (working with Tiago and Eduardo) found that these monkeys even break one stone on another in a way that produces sharp flakes reminiscent of those made by the earliest humans. They use stone tools for more purposes than any animal except us. And here was yet another example to add to the mix.

So what happens when a startled male has a stone thrown at him? On ten of the observed times, the stone actually hit the male, rather than falling short or missing him. Each time, the targeted capuchin turned and briefly chased the offending female, which from her perspective counts as a success. In a smaller sample of throwing events from 2012, the team also found that a female hitting a male with a stone resulted in them mating each time. While there is no clear data on whether stone throwing speeds up the process (it’s not a necessary step, as mating continues for every capuchin group, and only one has stoners), it has persisted for several years and so is unlikely to be entirely offputting for the males.

The limited occurrence of this unusual behaviour suggests that it was invented only within this one group—the Pedra Furada group—and it has stayed localised because female capuchins typically do not migrate away from their home. Still, re-invention is only a stone’s throw away…

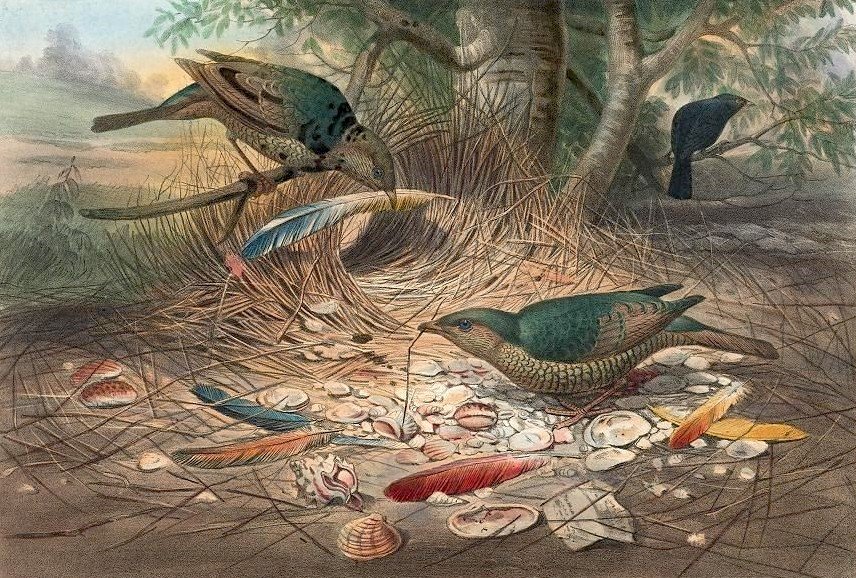

3. Bowerbird blues

Our final stop on this tour is with a true artist. Bowerbirds gained their common name from the spaces that males build as part of their efforts to woo a lady bird. These males, found in Papua New Guinea and Australia, typically create both a stick structure enclosing an open space, and a surrounding collection of colourful objects (a few species across the eight known bowerbird genera do neither, but that’s unusual behaviour for the group). Together, the objects and built environment shape any visiting female’s perception of the male’s movements as he attempts to convince her to mate with him. Developing their skills in this area can take years of practice, and could be considered the male bird’s life’s work.

Across many variations, the formation of these sites involves deliberate selection of both the objects themselves and their placement within the performance space. At first glance, though, this behaviour seems to fall closer to construction activity than tool use. This would put bowers in the same category of behaviour as beaver dams, termite or wasp nests, and other animal-manufactured environments. Why include them in a blog about tool use?

The answer is that those objects aren’t always a passive part of the display. They’re not just a pretty carpet, or a lure to grab the eye of a passing female. For example, consider the male satin bowerbird (Ptilonorhynchus violaceus) of eastern Australia. That’s him in the background of the 1860s painting at the top of this post, although that particular individual lived far from home in London’s Regent’s Park zoo. His species favours blue objects above most other colours, which nicely brings out his violet eyes and blue-black glossy feathers. Once the female is watching from within the constructed bower, he makes a series of dance moves and calls, some of which prominently include displaying objects:

This foreplay is more subtle than that of the male dolphins or female capuchins. The tool use in this case is an enhancement, directing the eye and capturing the attention (and hopefully future offspring) of the visiting female. The bird may pick up and put down objects as he displays, and even toss them about, but I haven’t heard of any instances in which the dancing bowerbird deliberately throws the object directly at the female. Given the care with which females approach the bower, and the time they take to select a mate from the numerous performances they attend, any male suddenly lunging at her with a tool may well be ending the relationship before it starts.

And that completes today’s tour. We’ve seen examples of tool-based attraction that may be new or confined to a few animals (the male dolphins), or perhaps spreading but confined within a single group (the female capuchins), and well-developed ones that obviously have a long evolutionary history throughout an entire set of species (the Ptilonorhynchidae or bowerbirds). All tool use starts somewhere, though, and even the smallest advantage in the game of life adds up in the end.

Speaking of life, here’s David Attenborough from the BBC Life program to take us out, with the trials of the Vogelkop bowerbird (Amblyornis inornata) of western New Guinea:

Sources: Allen, S. et al. (2017) Multi-modal sexual displays in Australian humpback dolphins. Scientific Reports 7:13644. || Falotico, T. & E. Ottoni (2013) Stone Throwing as a Sexual Display in Wild Female Bearded Capuchin Monkeys, Sapajus libidinosus. PLOS One 8: e79535. || Proffitt, T. et al. (2016) Wild monkeys flake stone tools. Nature 539:85–88. || Madden, J.R. (2003) Male spotted bowerbirds preferentially choose, arrange and proffer objects that are good predictors of mating success. Behavioural Ecology and Sociobiology 53:263–268. || Borgia, G. (1995) Threat Reduction as a Cause of Differences in Bower Architecture, Bower Decoration and Male Display in Two Closely Related Bowerbirds Chlamydera nuchalis and C. maculata, Emu 95:1-12.

Main image credit: Josef Wolf; https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/252810 || Dolphin image credit: Josh Smith; https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/article/dolphins-sex-mating-sponges-courtship || Dolphin video: University of Western Australia; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4ghGI-lIE9Y || Capuchin image credit: Falotico & Ottoni (2013) Capuchin video: Tiago Falotico;https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NcNq_mXragU || Bowerbird image credit: Mark Sanders; https://www.flickr.com/photos/colonel_007/49936478922/ || Bowerbird video: BBC Life; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=E1zmfTr2d4c