1903 | California, USA

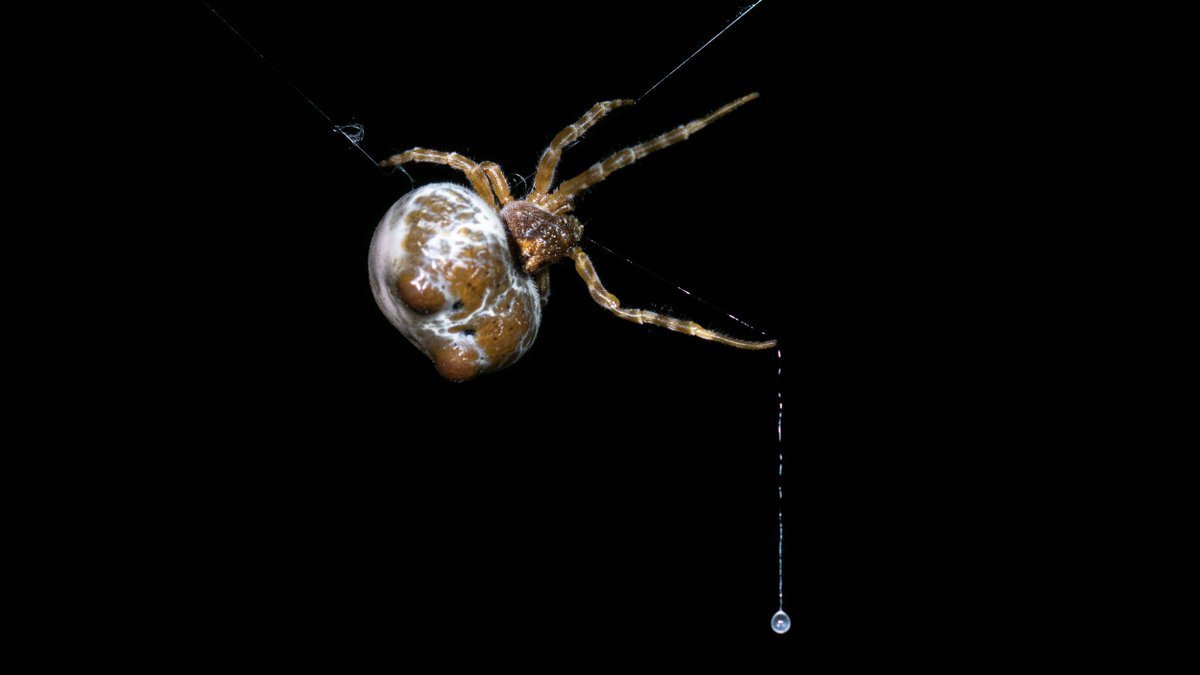

Bolas spider (family Araneidae) web slinging

Our story today is one that’s replicated nightly, in many places around the world, by many related species. But perhaps it’s not one you’ve heard before. It’s the tale of the bolas spider, and her elegant, deadly hunting weaponry.

A most wonderful operation

The sequence of events goes like this. A female spider spends her days pretending to be a blob of refuse, or perhaps a snail, sitting perfectly still with legs tucked in and holding firmly to a leaf. (The males are small and not good for much, let’s ignore them.) She spins cocoons to hold her eggs, but otherwise waits, visible but ignored as being just a bird dropping, or some other untasty specimen.

Come nightfall, though, the spider gets to work. She releases a single trapeze line, anchors it and walks out along the tightrope. In the centre of the line she hangs, and bit by bit creates a complex, tightly bundled thread, bound up in a sticky droplet. The droplet is itself attached to a single silk strand that she lengthens, takes hold of, and dangles.

By and by a moth approaches, a male moth as it happens. The moth is there because he’s been tricked into thinking that there is a female of his kind somewhere nearby. The spider has released a pheromone that performs that trick, with some spider species even able to vary the pheromone they produce according to the moth under predation.

And so the moth wanders close, too close. The spider whips the held thread around and outwards, and the droplet expands instantly into a sticky elongated mass of tangled silk. Often enough, the weapon strikes its target, and the moth goes from amorous to panicked in an instant. Incapable of extracting himself from the gluey string, he is reeled in, bitten, paralysed and bundled into a shroud to await his fate.

This isn’t passive web building, but active manufacture and use of a hunting tool. The BBC’s Life in the Undergrowth shows us just how it works:

There are perhaps four genera of bolas spiders, depending on which taxonomist you ask. Their ranges cover central and southern Africa, Asia from India eastwards (including Australia), and both North and South America. The name bola comes from Spanish for a ball—and in turn from the Latin bulla or bubble—while a ‘bolas’ more specifically refers to a thrown hunting tool in which weights are connected by a rope. When released, the bolas spins and then wraps around the legs of whichever prey (or person) you were trying to immobilise. The Inca used them in warfare, and Patagonians used them from horseback to hunt large flightless birds such as the rhea. The parallel to the spider behaviour is clear, although there is sadly no evidence that humans learned this tactic from their arachnid compatriots.

Patience rewarded

The fact that these spiders can precisely mimic their prey’s chemical attractant is a key part of making the ambush work. That pheromone link was confirmed in 1977 by William Eberhard, now an emeritus scientist at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute in Panama. If you want to delve further into how and why spider webs are made, I can recommend Eberhard’s detailed 2020 book on the topic, which is naturally called Spider Webs. (It’s a large and thorough work on a complicated topic; as the author noted in one interview: ‘I seriously underestimated how difficult it would be’.)

The thing is, the very first scientific report that we have on bolas spiders already went most of the way to figuring out what we now know about this behaviour. That study was by Charles Hutchinson in the journal Scientific American, in September of 1903.

Compare Hutchison’s illustration from that report with the photos in this post - it’s clear that he had deep familiarity with his subject:

Hutchinson was writing about a species that he called Ordgarius conigerus, now usually termed Mastophora cornigera. He lived in Glendale, California, and was in the habit of spending his evenings watching the local wildlife. Although not a professional entomologist, Hutchinson was a close observer and detailed note-taker. Here’s the section of his report that describes the spider making her bolas:

Pressing the tips of its hind legs firmly upon the thread it pushes each leg backward, alternately, allowing the thread to slip between the short, stiff hairs which clothe them. With each extension a small quantity of viscid matter is pushed outward and away from the abdomen as far as the leg will reach. At the end of about twenty seconds, during which time each leg is extended eight or ten times, there results a globule.

And this attention to detail doesn’t stop at visual observation. For example, on the sticky globule itself:

The globule is whitish or watery in appearance, apparently odorless, and may be tasteless, though I fancied that I detected a slight peppery taste.

I have yet to find any other study that mentions how the weapon tastes. Although the spider herself may know, because—as Hutchinson saw—if a moth isn’t captured within a half an hour or so she can draw the ball back up and ingest it, before forming a new tool and beginning the wait anew. Later work by William Eberhard showed that evaporation causes the bolas to shrink over time, so this is actually a plausible example of tool maintenance on the spider’s behalf.

This bolas spider hasn’t reached the ingestion stage just yet, but I’ll include it here as it’s named after Charles Hutchinson—Mastophora hutchinsoni:

Hutchinson realised that moth capture works best only when the moths are extremely close to the spider, and reasoned that there could well be a chemical message passing from hunter to hunted. Despite a lack of complex chemical analysis, and 74 years before it was confirmed, he made some progress:

Whether it is some agreeable odor emitted by the arachnid or from its weapon, or whether the prey comes accidentally within reach is a problem of some interest. While the evidence gathered is wholly negative it seems to support the conclusion that the spider does emit such an odor. None, however, is perceptible to human nostrils except when the arachnid is roughly handled, when a very noticeable sour-bitter odor is encountered. This arises from an amber-colored emission from the mouth. Small pieces of cloth scented with this failed to attract a single moth, though several passed by at no great distance.

Catch them all

Why did it take so long to follow up on this pioneering work? Somewhat surprisingly, Hutchinson’s report went largely unremarked, and was essentially forgotten for the next half century. When Willis Gertsch, curator of insects and spiders at the American Museum of Natural History wrote about bolas spiders in 1955, he had only known of their hunting behaviour for the previous few years, and then only because Charles Hutchinson happened to tell him about it directly. Gertsch is the one who ended up naming a species in Hutchinson’s honour, which seems fair.

You may think that such a fascinating topic would be hard to lose track of, and yet, as sometimes happens in science, exactly the same obscurity befell the second bolas-swinging spider report. That was published in 1922 by Heber Albert Longman, Director of the Queensland Museum in Australia. Longman’s paper was based on observations in his Brisbane garden, and it supports and replicates much of Hutchinson’s work, albeit with a larger section on how the spider constructs its egg cocoons. Longman was looking at a different bolas species of course—in his case Dicrostichus magnificus or the ‘magnificent spider’—but he was seeing the same drama played out, based on the same script:

From its slender bridge it would spin a filament, usually about one and a-half inches in length, which was suspended downwards; on the end of this was a globule of very viscid matter, a little larger than the head of an ordinary pin, occasionally with several smaller globules above. This filament was held out by one of the front legs, the miniature apparatus bearing a quaint resemblance to a fisherman's rod and line. On the approach of a moth, the spider whirls the filament and globule with surprising speed, and this is undoubtedly the way in which it secures its prey. The moths are unquestionably attracted to an effective extent by the spider; whether by scent or by its colour we cannot say.

The ‘we’ in that last sentence is Heber and his wife, Irene, who was also the first woman parliamentarian in Queensland. Hutchinson and the Longmans both experimented with catching moths themselves and then sticking them to the spider bolas as it waited, showing that it was the moth’s vigorous fluttering, detected by hairs on the spider’s legs, that triggered the attack. In Longman’s words,

The spectacle of the moth fluttering up to the spider, sometimes two or even three times before it was caught, is one of the most interesting little processes which the writer has ever witnessed in natural history.

The point of dwelling on these overlooked reports is not to say that earlier work is somehow more important than later studies. Instead, it’s to emphasise (as I’ve often tried to do in this blog) the value of curious non-specialists simply taking the time to pay close attention to the natural world around them. There is no reason that the next extraordinary and previously unremarked animal behaviour couldn’t be found by you, in your garden, local park, nearest beach or even a crowded city centre. Everywhere there are animals, in fact. Just pull up a chair, have a notebook or phone camera handy, and start your own voyage of discovery.

Further viewing

Want more? Here’s a complete 5 minute sequence of moth predation, capture, venomous bite, waiting for the venom to take effect, and prey wrapping by a Mastophora timuqua spider in Ohio, USA (filmed by Richard Bradley):

Sources: Hutchinson, C.E. (1903) A bolas-throwing spider. Scientific American Sept. 5, 1903, p.172. || Eberhard, W. (1977) Aggressive Chemical Mimicry by a Bolas Spider. Science 198:1173-1175. || NHBS (2020) Interview with William Eberhard; https://www.nhbs.com/blog/william-eberhard-spider-webs || Eberhard, W. (1980) The Natural History and Behavior of the Bolas Spider Mastophora Dizzydeani sp. n. (Araneidae). Psyche 87:143-169. || Gertsch, W. (1955) The North American bolas spiders of the genera Mastophora and Agatostichus. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History, vol. 106, article 4. || Longman, H.A. (1922) The magnificent spider: Dicrostichus magnificus Rainbow. Notes on cocoon spinning and methods of catching prey. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Queensland 33: 91-98. || Turner, S. (2005) Heber Albert Longman (1880-1954), Queensland Museum scientist: a new bibliography. Memoirs of the Queensland Museum 51: 237-257.

Main image credit: JCIV; https://www.flickr.com/photos/jciv/50428853937 || Second image credit: Richard Bradley; https://spidersinohio.net/bolas-spiders || First video credit: globalzoo; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EWec266Lo3Q || Third image credit: Hutchinson (1903) || Fourth image credit: Richard Bradley; https://spidersinohio.net/bolas-spiders || Second video credit: Tapinopa; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zvtZIRlLmWU